Prohibition Cocktails: The Literature of Libations

December 5—also known as Repeal Day—marks the end of Prohibition back in 1933.

Mark Twain’s observation “It is the prohibition that makes anything precious” simply doesn’t apply to alcohol anymore. These days it probably wouldn’t surprise anyone to find a selection of craft cocktails on the menu at a Chili’s.

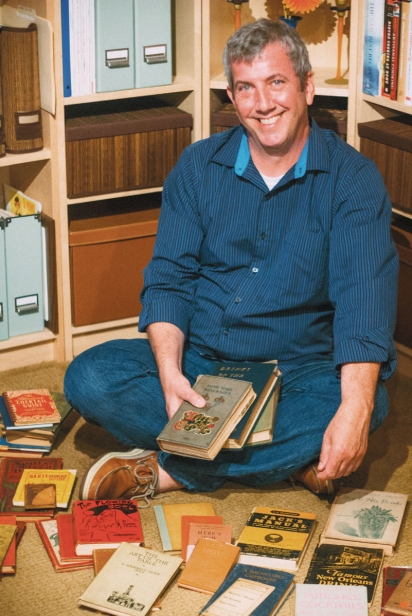

One thing from the bygone era of Prohibition that does remain rare is its literature. Beverage enthusiast Steve Jaffe is doing his part to preserve a record of this significant cultural moment in our country’s history, 1920–33.

Tucked in a quiet neighborhood in the east end of Ventura, Jaffe’s home has a small room dedicated to a collection of rare and scarce cocktail recipe books from the Prohibition era. To learn more, I spent an afternoon in his company.

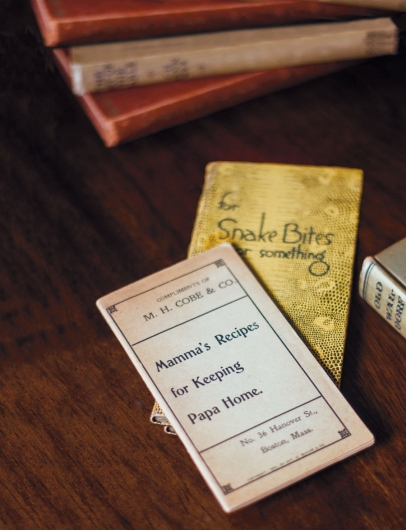

The first book he showed me, Mamma’s Recipes for Keeping Papa Home, dates from 1901 and focuses on one significant factor that led to Prohibition. Compliments of M.H. Cobe & Co., a Massachusetts-based liquor importer and bottler, this advertising booklet addressed the angst of women whose husbands had abandoned them for saloons, one factor that fueled the Temperance movement. “If the within instructions are strictly adhered to, success will necessarily follow,” states the back cover.

Despite the creativity of the tactic, it wasn’t enough to stem the tide; 19 years later Prohibition began.

Cocktail literature now turned to preserving the knowledge that bartending professionals feared would be lost forever, as many among their ranks fled abroad to continue to work. Albert A. Hopkins’ Home Made Beverages is one such example; Jaffe notes that it has been cited by several collectors as the last book published by a major publisher before Prohibition took effect.

Jaffe’s copy—purchased on eBay for $5 (including shipping)—is well worn, but there’s real treasure tucked inside, from Prohibition-related newspaper clippings to a recipe for an apricot and raisin wine—made with sugar, yeast and water and fermented for two weeks—typed up on “Bureau of Internal Revenue Office of Special Agent” letterhead.

“You can just the feel the life that the previous owners had,” says Jaffe, who is restaurant manager of Ojai Ranch House and relishes this volume in his collection as much as those in mint condition.

During Prohibition, citizens in small towns and rural areas who were after a drink turned to home brews, whether from a Special Agent’s recipe, a neighbor’s basement still or a wine brick—a block of grape concentrate that conveniently featured instructions for what not to do with it, namely dilute it and leave in a cupboard to ferment.

In big cities, affluent residents had easy access to cocktails in speakeasies. As an aside, America became the world’s largest importer of cocktail shakers during Prohibition.

Still, precautions were taken. Herbs, honey and fruit juice were used to mask the smell of alcohol—and the taste of bathtub gin. High-end New York restaurants took the masquerade one step further, serving cocktails in teacups to regular patrons.

During Prohibition, publishers of cocktail books employed similar creativity in how they distributed their material. Handing me a slim volume covered in faux snakeskin, Jaffe explains that Good Cheer was a pre-Prohibition cocktail handbook rebound during Prohibition to look like an instruction manual, helpfully retitled For Snakebites—Or Something.

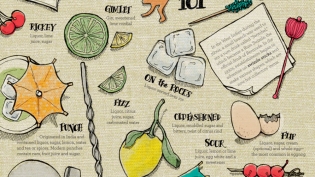

I left Jaffe’s library eager to put my Prohibition-era book learning into practice and headed to Sly’s in Carpinteria. Its menu lists each cocktail with the year of its invention, revealing that the Negroni, Bloody Mary, Gimlet, White Lady, Hemingway “Papa Doble” Daiquiri and the reputed hangover cure Corpse Reviver #2 all first came to life during the Prohibition era.

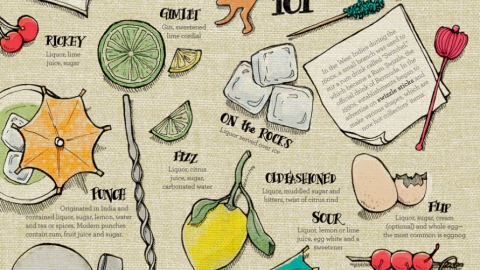

Chris Chinn, Sly’s bar manager, describes Prohibition-era cocktails as being characterized by simplicity—no more than four to five ingredients per drink—and booze. “Most have an aromatic ingredient like Angostura Bitters, Campari or the base spirit of the cocktail itself, usually gin.”

“Bitters were prescribed as medicine during Prohibition and they have a high alcohol content ... easy to see how they landed in so many drinks.”

Not wanting to need a Corpse Reviver #2 the next day, I limited myself to a White Lady and a Gimlet, both variations of gin and citrus juice. Fresh from my education at the hands of Jaffe and Chinn, I could taste a fabled era of American history with every sip.

Did You Know?

During Prohibition, pharmacists could legally dole out whiskey by prescription for everything from anxiety to influenza. Bootleggers realized the opportunity, and, not surprisingly, the number of registered pharmacists in New York State tripled

Source: Prohibition: Unintended Consequences, PBS.org

During Prohibition, attendance rose at churches and synagogues because wine was allowed for religious purposes.

Source: Prohibition: Unintended Consequences, PBS.org