The Kids are All Right

Chefs turn passion for goats and gardening into Oats & Ivy Farm

Amanda Nuñez and Scott Peterson drew a few bemused looks when they made rest stops while traveling from Oregon to California in their Toyota Corolla. When they unlatched the pet crates inside their vehicle and took their four-legged charges out for a stretch, it wasn’t dogs that came out, but three little goats.

I sat with the couple one brisk morning on a bench next to the goat pen on their Somis farm, with their rescued Border Collie mix, Quinn, bouncing eagerly in her enclosure on one side and an avocado orchard on the other. Now 28 years old and married nearly three years, Nuñez and Peterson gave me the rundown on less than a decade of geographical and culinary adventures that most people won’t experience in a lifetime (like traveling long distances with goats in a car).

Nuñez, originally from San Diego, and Peterson, who grew up in Long Beach, met as students at the Culinary Institute of America (CIA) in Hyde Park, New York. Platonic friends who roomed together in a tiny New York City apartment with other students during their school externships, the two eventually fell in love.

Back in California, they worked at the Ojai Valley Inn & Spa, and then went to the Four Seasons in Jackson Hole, Wyoming, where Peterson had a stint as a sushi chef. Next, they were in the “middle of nowhere,” Arizona, on a camping trip, when their intermittent cell phone service suddenly kicked in long enough to receive a call from their Four Seasons sous chef, inviting them to move to Seattle, where they helped open Restaurant Marron, which specialized in intricate tasting menus.

Nuñez, who had been bitten by the cheesemaking bug while in culinary school, began looking for opportunities through World Wide Opportunities on Organic Farms (WWOOF), an organization that connects people who want to learn farming with those who are seeking volunteer help.

She discovered Gianaclis Caldwell’s Pholia Farm, an approximately 24-acre goat farm and dairy in Oregon. Though Caldwell wasn’t able to accommodate Nuñez and Peterson at first because she didn’t have room for them to work on the farm, the pair, undaunted, found their own place and drove to the farm every day to learn the trade.

“I thought, ‘Someday, when I retire, I’m going to have goats and a little farm,’“ explains Nuñez.

With Caldwell as their mentor, the pair became enamored of the idea of raising goats much sooner than planned. Nuñez became something of a goat doula after “kidding” season, learning to help goats deliver their offspring, which usually number two or three per pregnancy. It was just over a year ago that the couple purchased three dairy goats from Caldwell to bring back to the Peterson family’s 10- acre property in Somis.

It was there that Oats & Ivy Farm was born, homage to “Mairzy Doats,” sung to Nuñez as a child by her mom.

The property was originally purchased by Peterson’s late grandfather, Doug Peterson, a commercial pilot and World War II veteran, for his retirement. It includes six acres of avocados and the farm, where the couple has a flock of over 70 egg-producing ducks and chickens and their growing goat herd, now at eight.

They took several of the goats out of their pen for me to meet up close. They’re spunky yet gentle, perhaps in part because Nuñez’s affection for them is apparent as she says their names and points out their distinctive coloring and personalities.

“They’re sassy, but all real sweet,” says Nuñez. “They want attention and love. They’re good therapeutic animals.”

Nuñez and Peterson reside in a home on the property where they are in close proximity to their herd, which are housed in a comfortable barn the couple built, with pens, kidding area and a milking parlor.

The goats were bottle-fed in order to form attachments with people. One is a purebred Nigerian Dwarf, and the others are a mix of LaMancha and Nigerian Dwarf, which make for a manageable, compact-sized goat.

When one of the females goes into heat, Nuñez drops everything to bring her to a buck that lives on a small farm in Hesperia. One kid was born this winter and two goats are pregnant, due in April.

“Like any mammal, you have to have kids to [stimulate] milk,” says Nuñez.

She creates goat-milk soaps that she sells in her Etsy store, and at the Camarillo Certified Farmers’ Market and Ragamuffin Coffee Roasters in Newbury Park. She hopes eventually to have a licensed creamery where she can make and sell cheeses.

With strong support from the Peterson family, the pair is constantly tossing ideas back and forth on how to make the best use of the property. They are considering thinning the avocado orchard and replacing the trees with other crops, and already have a garden for seasonal vegetables.

I toured the property—and it was quite a hike—with walking paths that run past the goats’ area and avocado orchard, and up and over slight hills where there are a number of outbuildings, several homes and large trees, some of which provide leafy treats for the goats.

“Our dream for the property is for it to be super-multifunctional,” says Peterson. “We have a lot of ambition. We’re trying to do a better job overall of producing really good produce for the animals’ sake.”

And they remain true to their culinary roots. The couple, who have outside jobs and also work occasionally as private chefs, have created a pop-up restaurant concept they call Spoon Barn. Peterson, who works at Ragamuffin, credits owners Shawn and Sarah Pritchett with helping them bring their Spoon Barn dinners to fruition.

“We want to be resilient for the community and everyone living here,” says Peterson. “Ragamuffin itself is a huge community-based business.”

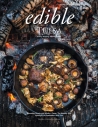

Crafting the 24-seat tables themselves in Peterson’s grandfather’s workshop, the pair have held three Spoon Barn dinners at Ragamuffin, and hope to expand them, either by adding more tables, or by having two separate dinners per evening. Gourmet, multicourse menus are seasonal and feature locally sourced ingredients. Dinners have included their takes on gazpacho, dumplings, lamb, pork belly, confit, shellfish and more.

The next dinner is planned for spring, either before the second batch of kids is born or when they’re old enough that Nuñez and Peterson can leave for an evening.

The couple is constantly exploring possibilities for growth, while further educating themselves about organic crops and sustainability. They’re hoping to breed goats on their farm and add some pigs.

“This whole lifestyle brings you joy—growing your own food and raising your own vegetables,” says Nuñez. “Now we’ve got some roots. We’re trying to figure out how to sustain this. We want to be part of the community, and we’re trending toward living better and eating better.”

What’s a “Spoon Barn”?

The name is from this “wonderful and important concept” of using everything to the fullest, says Nuñez. When a barn is falling down, the wood is used to build a table. As the table starts to wobble and break, turn it into a chair. When the chair is nearly finished, a spoon is carved from the wood.

“It is about making the most out of what we have around us and bringing new life to old things,” she says.

For more info, visit OatsAndIvyFarm.com.