Called to Feed the World: Future of Farming

New book offers honest look at the future of farming

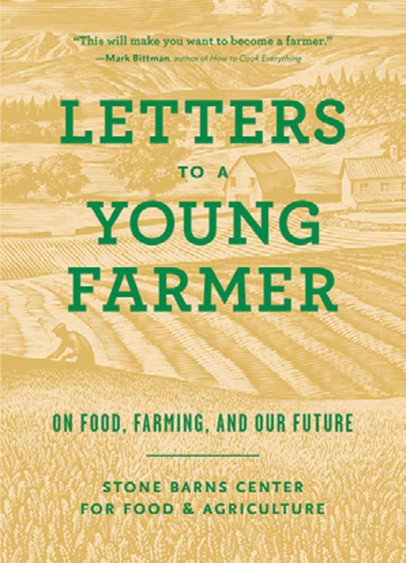

Letters to a Young Farmer:

On Food, Farming, and Our Future

Stone Barns Center for Food & Agriculture

Princeton Architectural Press, 2017

Ten years ago I went to hear Julee Rosso, co-author of the renowned Silver Palate Cookbook, speak. I’ll always remember how she concluded her remarks: “Restaurant chefs get all the glory,” Rosso said, “but farmers are the true rock stars of the food world.”

Anyone who has tried to find parking at a farmers’ market knows that these rock stars draw crowds. CSA subscriptions and farm-to-table dinners regularly sell out, and national supermarket chains carry local produce. In so many ways, it seems that farming is thriving and well supported.

Yet farming is an endangered lifestyle. Specifically, the rock stars are aging. Letters to a Young Farmer, a new book produced by the Stone Barns Center for Food & Agriculture, warns that we’re about to experience the largest retirement of farmers in U.S. history. The average American farmer is 58.3 years old, and only 6% of farmers are under age 35.

As farmers retire, more than 400 million acres of farmland will change hands in the next 20 years—roughly four times the size of California and more than half the total farmland in the country. Soon there will be fewer than two million farms in the United States, the fewest we’ve had since the early 1800s. And of course, climate change and its accompanying weather extremes is making farming a riskier business than ever before.

Letters arose from concern for the next generation of American farmers, who are inheriting all the environmental and economic problems created over past decades and yet on whom we are relying to feed us in the future. Its stellar list of 36 contributors includes Barbara Kingsolver, Michael Pollan, Rick Bayless, Bill McKibben, Wendell Berry, Alice Waters and experienced farmers whose families have farmed sustainably for generations.

While it was the celebrity names that drew me to this book, it was the farmers’ epistolary essays that kept me turning pages late into the night. Brimming with advice, encouragement and a dose of harsh reality, these essays off er a fascinating window into modern farming. Today’s farmers work daily as “sweaty, blue-collar laborers,” in the words of contributor Mary-Howell Martens, but also are proficient in diverse fields such as accounting, marketing, veterinary medicine, mechanical design, computer science, meteorology, fertility management, botany, and the list goes on.

As a profession, farming is almost never lucrative but, as you might guess, farmers are not in this for the money. Underlying these individuals’ commitment to the land and the people it feeds is a deep, heartfelt sense of vocation. This sense of “call” was truly inspiring, as were the achievements of these successful producers: All of them, whether they raise livestock, poultry or fruits and vegetables, have been farming sustainably, often organically, for decades. Despite a prevalent narrative that says “Big Ag” is the answer to the problems with our food system, these farmers’ lives bear witness to an alternative path. (Though many essayists warn against demonizing “Big Ag” and are far from sanctimonious about their farming methods.)

I am not a farmer but a consumer, and as I read Letters I wondered what I might do to help ensure that our food system has a healthy future. Some of the solutions are obvious: Be willing to pay more for produce that is grown locally, support food cooperatives, buy a share in a CSA. As the oft-quoted Wendell Berry wrote, “Eating is an agricultural act.”

But becoming an activist for our producers is equally important: As consumers, we should become well-informed about the big-picture issues in agriculture and read up on how their local politicians support or hinder successful farming. Get involved and be an advocate for your local food system.

As home cooks, writes Alice Waters in Letters, let us not forget that our kitchen and dining rooms are healthier, more vibrant places when they are vitally connected to what was happening in the field. On that note, I will share a recipe idea from Letters, which appears in an essay authored by Rick Bayless. He writes of a famous cooking school in Ireland that teaches its first recipe not in the kitchen but in the school’s garden. And that first recipe is? Compost.