Unlocking Opportunities

Jail’s culinary program provides tools for a fresh start

A black-handled chef ’s knife is locked and cabled, its tip out of sight, tucked under the base of a stand mixer sitting on the edge of the stainless steel prep table. A sheriff’s deputy stands a few feet away, watching the activity on the outskirts of the 10,000-square-foot kitchen at the Todd Road Jail in Santa Paula.

Sterile is the best description of this room—white, fluorescent lights, no windows, no decor.

Primitivo Pina doesn’t seem to notice. He’s hunched over his sugar cookie, focused on the intricate details of a snowman. He uses a rubber spatula to paint on the base of white icing. For decorating, his tools are rudimentary: a plastic ice cream tasting spoon and spatula, and a container with a needle-nose tip to create a pinkish-red scarf, green hat and black placket down the snowman’s middle.

“What’s next?” asks Chef Amy Tyrrell, as the two lean in to size up the project in process. She calls him “Mr. Pina.” He calls her “Chef,” per protocol in a professional kitchen.

“We don’t have the tools a culinary program usually has, like piping bags,” says Tyrrell, who teaches the class through a partnership between Ventura Adult and Continuing Education (VACE) and the Ventura County Sheriff’s Office.

It’s a safety precaution that certain small tools like piping tips are not allowed. “It’s a challenge, but we’re learning to be artistic with the tools at hand,” she says with her trademark enthusiasm.

This is the fourth class of inmates to go through the vocational culinary program at the jail, which combines academic learning and hands-on cooking. The program’s goal is to train the students on all stations of the kitchen so they can get a job in the culinary field when they’re released. Employment is so important in reducing recidivism, Tyrrell tells me.

Pina was in the culinary program at Pacifica High School in Oxnard as a senior. After graduating early, he started hanging out with the wrong crowd. One thing led to another and here he is, and not for the first time. He knows too many people who are in jail. Pina is determined that when he gets out in mid 2018, he won’t be back. He plans to work with VACE to get a job—any job—in a restaurant to start his culinary career.

His ultimate goal, he says, is to be on the TV culinary competition show “Chopped.”

“I like the challenge of the random ingredients,” he says of the show’s premise of cooking on the fly with a handful of ingredients not revealed until it’s time to cook.

Next to Pina, Miguel Ochoa carefully places colorful candy decorations on his sugar cookie. He’s quieter, not as outgoing as Pina. Perhaps it’s because this is only the second day in the kitchen and he’s new to baking. He’s more comfortable cooking the traditional Mexican dishes he learned from his grandmother, he says, like tamales, menudo and chili verde. Before even stepping foot into the kitchen, the students completed a four-week food safety class.

“I’m trying to get the most out of this class that I can,” Ochoa says.

There are 750 inmates at the Todd Road Jail on an average day; most of them are men. This facility is for nonviolent offenders. Their crimes tend toward drugs, theft and burglary and they’re typically incarcerated two to six years. (There are 175 women inmates at the jail on average.)

The four-month culinary program, launched in 2016, is only available to men at this point, though administrators hope to have a group of female inmates in the future. To be in the program, the inmates need to be “motivated and committed to making changes,” says Cecil Argue, Inmate Services programs manager for the Ventura County Sheriff’s Office.

They also need to demonstrate compliance with jail rules. In other words, they’re model inmates. Per VACE’s requirements, participants need to be able to work in the U.S., and have a high school diploma or its equivalent. If they don’t, they can concurrently earn their high school equivalency credential through VACE.

The idea for this vocational culinary program came in 2015 when Argue and Commander Ron Nelson reached out to Pat Doler, culinary arts coordinator for Career Technical Education at VACE, which already had a culinary program up and running. Doler and Tyrrell put pen to paper with jail administrators to outline the program.

They looked at everything: From curriculum development, equipment needs and learning materials to arranging appropriate security for VACE personnel, security controls on knives and sharp blades to scheduling time for the students to be in the jail’s kitchen at a time no other inmate was there working. Funding for the program was obtained from the Ventura County Adult Education Consortium through an Adult Education Block Grant (Assembly Bill 104). One thing that sets this program apart from other culinary programs for inmates in the state and nation is that it’s nationally accredited by the Council on Occupational Education.

The program’s curriculum follows the National Restaurant Association’s Pro-Start Program Levels 1 and 2, says Tyrrell. So when the students graduate, they have their ServSafe Food Handlers card (required for any food-service position), Prep Cook certification and Line Cook certification. They can opt to stay on and pursue their Managers ServSafe certification.

By the time they’re through the program, Ochoa and Pina will have a foundation in culinary basics. Like all the students who’ve been through the program, they will know knife skills, how to make mother sauces (the base on which all sauces are built), basic techniques in every station in the kitchen, food safety, procurement, shipping and receiving and food prep, say Tyrrell. She sources local and organic produce as much as possible for the cooking projects and talks about farm-to-table dining and ties to the community.

When the inmate is released, VACE provides employment guidance. “VACE has excellent relationships with local employers who are ready to give program graduates a chance,” Doler tells me.

Employment Development Department stats confirm that there are suitable jobs here. In 2014, there were an estimated 7,860 cooks and food preparation workers in Ventura County, according to EDD. The number is projected to reach 9,580 by 2024, an annual growth rate of 2.2%.

For the program, students meet twice a week; each day is four hours of lecture and two hours in the kitchen practicing techniques by making a recipe. The dishes they make are shared with each other and jail staff.

“Part of the program includes an emphasis on developing math, reading and writing skills, along with the professional skills of presentation and interviewing,” says Tyrrell, who owns Morsels as You Wish in Ventura.

Through 2017, 14 inmates have been through the program; two have been released from jail and have connected with VACE. While still incarcerated, they were accepted to the California Department of Corrections Fire Camp last year as cooks, plucked from a pool of 115 applicants.

This current group started with four inmates and within the first two weeks was down to just Pina and Ochoa.

I’m surprised the class is so small. Seems to me, people would clamor to take part in what looks like a life-changing opportunity.

“That’s us putting our outsider ideas on the issue,” explains Argue. “A jail is a different world with different rules.”

Blame peer pressure as one of the myriad reasons why.

“There’s a layer of dynamics inside a correctional setting that are very difficult for inmates to overcome. If they go against the mass populace they believe they’re putting themselves at risk,” says Argue, who’s been employed in various departments within the criminal justice system for 27 years. “If you have one good apple in a barrel of bad apples, it’s hard for the good apple to stay good and to influence the others.” The inmates who take a chance on the program, however, benefit way beyond job skills, says everyone I talk with.

“Over and over again, in every class, we see a new confidence gained, the joy and sense of accomplishment on the faces of the students when completing some of the most basic, yet fundamental tasks,” says Doler.

Jails are notoriously divided, says Argue. Inmates don’t always come together and get along, he says. In the culinary program, it’s a different story.

“You have inmates coming together in a class oftentimes of different backgrounds, cultures, ethnicities, geographically by neighborhood, and there’s the expectation that they learn to work together,” says Argue. “One of the big pieces that we’ve seen is that you have inmates taking instruction from other inmates who in the past they probably wouldn’t have listened to or have respected as a leader and an instructor.”

“They can shed their past and move forward,” he adds, which can mean dealing with substance abuse, anger management and family issues.

At a graduation ceremony this fall for a previous class, Tyrrell spoke affectionately about that class’s three graduates and another inmate in the program as a mentor. “We’ve all had moments of laughter, we’ve all had moments of aha! And we’ve all had going-to-cry moments,” she says.

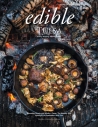

Following the ceremony held in the portable classroom where the book learning takes place, they served a spread of dishes they’d prepared for the occasion: herb-roasted tri-tip, summer vegetable risotto and roasted asparagus. Tuscan melon soup was the amuse-bouche. Tres leches cupcakes with a mascarpone frosting capped the meal.

Pina will get to this point. For today, he’s happy with the results of his cookie project.

“It would have been better with the utensils, but without the utensils I think it’s great.”

It is.