People to Watch in 2016 and Beyond

Meet four local professionals whose connections to food are influencing how we eat and what we eat. They’re a diverse group of change agents who are busy working behind the scenes to move the conversation about food forward for everyone’s benefit, now and into the future. The best part is that they’re doing it out of passion, not to gain recognition. So we’re training our spotlight on them to honor their endeavors.

CHRIS MASSA

Why: He’s working to get fresh produce into our children’s schools.

With tireless enthusiasm and energy, 27-year-old Chris Massa has been pivotal in getting farm-fresh produce into six school districts within Ventura County. (And hopefully more in the coming year.)

Massa came to Ventura two-and-a-half years ago to work at Food-Corps, where the position revolved around nutrition education, school gardens and working with local farmers.

Thanks to a specialty crop block grant from the California Department of Food and Agriculture (CDFA), Massa is now employed by the Ventura Unified School District, fiscal sponsor of the grant, as its farm to school operations specialist. (According to CDFA’s website, specialty crop block grants are designated to enhance the competitiveness of California specialty crops, which include fruits, vegetables, tree nuts, dried fruits, and horticulture and nursery crops.)

The school districts covered by this grant include Conejo Valley, Port Hueneme, Ojai, Oxnard, Rio and Ventura, where Massa is in constant communication with a project coordinator, nutrition specialists, cafeteria workers and the farmers who provide the produce.

The Ventura County Farm to School collaborative—a diverse group of integral stakeholders that supports the procurement of local produce, nutrition education and school gardens—would like to add at least two more districts in 2016, says Massa. “We will be reaching out to Fillmore, Santa Paula, Ocean View [in Oxnard], Oak Park, and Pleasant Valley [in Camarillo], but it will be an open invitation to all Ventura County school districts.”

Massa says he’s “kind of like a liaison” because he works with farmers to procure fruits and vegetables, and the nutritionists who work with the students to do taste-testing. “My official duties are identifying new farmers, working with them to get their products into schools, and working with them to grow specifically for schools.” He also works with cafeteria staff to see what their needs are so they can use the products he’s working to bring in.

Massa emphasizes that making sure K—12 students get their recommended portions of fruit and vegetables is a group effort, from the farm worker in the field, to the farmer-owners, to the school districts’ child nutrition services directors and cafeteria employees.

“We are educating students, parents and community members that agricultural workers and school kitchen staff work really hard to feed our nation and feed our kids so, therefore, are some of the most valuable members of our society.”

Currently on his agenda is to talk to superintendents in the county about building a working farm on at least one school district’s property for the 2016—17 school year.

“It’s great when I can introduce them to farms in the area, but even better when they are growing the food themselves. Many have their own gardens, but I would love to see them have a half-acre farm. This is something I’m going to be pushing for the new year, where kindergarten through high school students can grow their own food, and it can be donated back to the cafeteria,” says Massa, who has a passion for “promoting healthy eating, a just food system and stewardship of this beautiful planet we all inhabit.”

ROSE HAYDEN-SMITH

Why: She distills down copious amounts of foodpolicy info to help us stay informed.

Rose Hayden-Smith is in a hurry. Not just during our interview; she is in a hurry in general. The long-time Ventura garden educator and historian who holds the reins of UC Food Observer, a University of California Global Food Initiative to engage in the food policy debates swirling in the digital space.

Launched in 2015, the platform features original content, often interviews of food movement leaders, as well as shared content.

“UC has given us great freedom and latitude,” Hayden-Smith says. “We’ve had no pressure to push UC science or personalities.” With a second year looming, she plans to build on that success. The website (UCFoodObserver.com) will be refreshed, additional support will be added, new content developed and new interviews booked.

Her position continues a long association with the University of California that began as an undergraduate at UC Santa Barbara, includes a doctorate in history and local work with the UC Cooperative Extension and 4-H. Despite that busy schedule, she published Sowing the Seeds of Victory: American Gardening Programs of World War I (McFarland, 2014).

In addition to the 24/7 demands of social media, she remains a sought-after speaker in her area of expertise: the Victory Garden movement during the World Wars, and the school garden programs that followed. Her emails include the tag “A Garden for Everyone.

Everyone in a Garden.” Adapted from a World War I program to promote agricultural self-sufficiency, the slogan captures her belief that understanding food production is an essential part of making good food choices.

Whether made by consumers, school children or policymakers, these choices require knowledge about our food system. Gardening is an opportunity to make a fundamental connection to the basis of our society’s health.

Being well-versed in national food and land policy gives her a unique voice in the agricultural county she calls home. “This is such an innovative place!” she exclaims, noting the county’s leadership in an ever changing palette of crops and growing practices. The county’s agriculturalists are innovative and responsive to changing and evolving situations.

“Ventura County was one of the first to have a county farm adviser after the passage of the Smith-Lever Act in 1914,” she adds.

While the history of this place keeps her interest, there is no doubt that her heart belongs to the produce. Her boundless enthusiasm peaks as she mentions a recent salad: “Wonderful, just wonderful! Greens, tomatoes, avocados! All of it from right here! From farmers I know!”

Reflecting on Ventura County’s record of progressive farm policy, the restless historian wonders aloud what might come next. A Food Policy Council? A larger role for Ventura in the national food dialog? A bold initiative in food waste? “We’re already a leader in school lunches, but will the effort expand?” she asks.

So often a leader, our community now has an opportunity to learn from the examples of others. Even if only 140 characters at a time, those lessons may be brought to us by Rose Hayden-Smith.

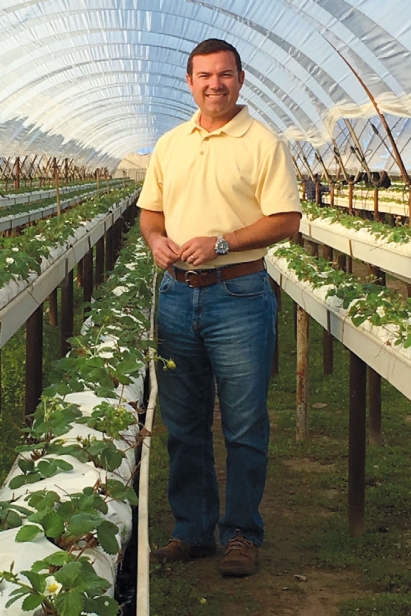

DAVE MURRAY

Why: Through hydroponics, he’s working on innovative ways to grow strawberries and making it easier for farm workers to harvest.

Seven years ago, strawberry expert Dave Murray took a trip to Spain that would forever change his perspective on growing and harvesting Ventura County’s top crop.

A longtime Ventura resident, Murray’s a partner at Andrew & Williamson Fresh Produce, which also owns Crisalida Berry Farms in Oxnard, where he specializes in finding new and innovative ways to grow a better, more flavorful strawberry. In addition to raising berries in the traditional open field, Crisalida has one acre of hydroponic strawberries and four acres of hydroponic raspberries.

“We were the first strawberry farm in Ventura County to install a hydroponic raised trough—which means the strawberries were above the ground—that was developed using the Spanish-style growing system,” says Murray, who chairs the research committee for the California Strawberry Commission.

With Spain facing similar crop-related difficulties as California, Murray and his colleagues knew there would be a need to expand upon their traditional open-field approach by using the Spanish concept of hydroponic systems under macro-tunnels.

One of the most damaging pests in strawberry production is Botrytis (AKA gray mold) caused by wet conditions like rain and fog, says Murray. In a hydroponic system under macro-tunnels, the fruit stays dry, reducing the need for materials that control this pest.

“With these systems you are able to double-use the water,” adds Murray. “You irrigate the strawberries in coco-fiber bags in raised-bed troughs, irrigating every two or three hours for five or six minutes, then we recapture the water and use it for our open field operation.”

Because the traditional method of growing strawberries allows the plants to spread out in soil more so than in the limited space of troughs, Murray implemented a feature to the hydroponic design he’d not seen in Spain.

“I believe that in order to be successful in terms of getting the yield up, you need to compensate by simply putting more plants per acre, or higher density,” he says. “So I developed a system so that there are more troughs per acre, so it gets my planting to up to 73,000 per acre. The Spanish system is about 43,000 per acre.”

The trough system is also more attractive for farm workers because they can pick berries in a field standing up rather than crouching.

Still, Murray and his colleagues are working on ways to optimize the new approach to improve cost-effectiveness and productivity and, most importantly, to provide consumers high-quality, flavorful berries. As this happens, this new approach to farming will become more mainstream.

“So many of the varieties we grow are based on an open field system, growing in a hydroponic system changes everything,” says Murray. “It’s really a matter of analyzing each variety, as there are newer and better varieties developed in the hydroponic system.”

“It’s important to reinvent in order to stay competitive and relevant in a changing world,” says Murray. “Our most valuable and our most scarce resources are water and labor and it’s important to innovate on both of those fronts.”

JUAN AGUSTIN

Why: He creates edible art that will cause people to pay attention to food.

We eat with our eyes first. Chef Juan Agustin clearly knows this, judging from a Pink Autumn Mosaic salad and every dish that arrived at the table during his Vincere Restaurant pop-up at Fresh & Fabulous Cafe in Oxnard.

A fundraiser for the National Breast Cancer Foundation, the meal was dressed in pink, with each course wherever possible working in the breast cancer awareness color.

The mosaic salad—an artistic arrangement of root vegetables, persimmon and grapefruit—sat on a brushstroke of goat cheese fondue and featured toast points dusted with dehydrated raspberry.

“My inspiration in how I plate is art and nature,” says Agustin, a line cook at Olivella at the Ojai Valley Inn & Spa who’s barely old enough to go to a bar. At the California-cuisine restaurant with Italian inspirations, he has works on plating dishes with Chef de Cuisine Andrea Rodella.

He’s just completing a three-month internship at Mélisse, a Michelin two-star French restaurant in Santa Monica, heading there on his day off. Everything he has learned, he puts back on the plate, he says.

“My goal with food is thinking outside the box. I always think how the guest is going to eat their dish and the first thing that will catch their eye,” Agustin says. As he describes how a fish dish with a brightly colored sauce and vegetables would be plated, he’s visualizing the elements, his hands moving around an imaginary plate.

He started his culinary education at Pacifica High School’s Culinary Arts Academy in Oxnard under his role model Linnea Howe and continued on to The Culinary Institute of America in New York, where he graduated in 2014.

“I was thinking about how I could make a difference in the world and thought it would be through food,” he explains, when asked why he switched his plans from medicine to cooking.

“In 2016, I envision myself as a leading sous chef at a nice, wellknown restaurant in the area—hopefully at Olivella.” He wants to do more pop-up events in the area that feature local farmers to further raise awareness within the community of their hard work and what they produce. “There’s a lot of great farming around here, a lot of great agriculture,” he says.

From here, his intended career trajectory includes becoming a chef de cuisine, studying cooking abroad and opening a bistro. If that goes well, then opening a “more modern place” that’s more food-focused and where dishes will take two to three days to prepare. He wants this restaurant “to be the best in the country.” All this by age 30.

He just might do it.

“I go by one saying [in life]: ‘simplicity but complex,’” he says. “Behind the simplicity there’s a lot of work involved. A lot of time, a lot of effort.”

Wendy Dager is a professional freelance writer known for her quirky takes on the most everyday subjects. She is the author of I Murdered the PTA (Zumaya Enigma, 2011) and I Murdered the Spelling Bee (Zumaya Enigma, 2012). To learn more, visit WendyDager.com.

Chris Sayer is a fifth-generation Ventura County farmer. He grows citrus, avocados and figs in Santa Paula and Saticoy. He serves on the boards of the Farm Bureau of Ventura County and Associates Insectary and blogs at SaticoyRoots.WordPress.com.