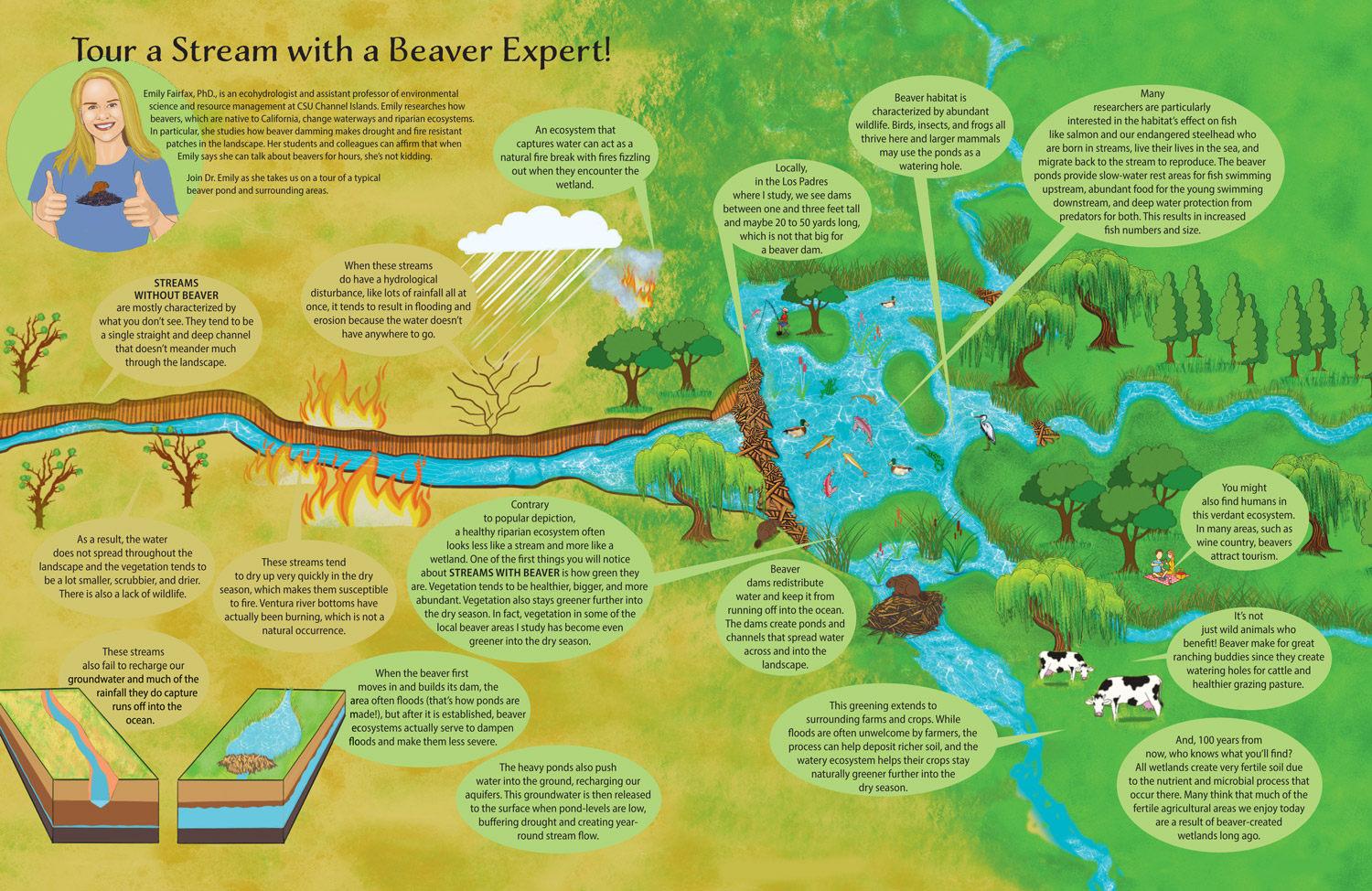

Tour a Stream with a Beaver Expert

Emily Fairfax, PhD., is an ecohydrologist and assistant professor of environmental science and resource management at CSU Channel Islands. Emily researches how beavers, which are native to California, change waterways and riparian ecosystems. In particular, she studies how beaver damming makes drought and fire resistant patches in the landscape. Her students and colleagues can affirm that when Emily says she can talk about beavers for hours, she’s not kidding.

Join Dr. Emily as she takes us on a tour of a typical beaver pond and surrounding areas.

STREAMS WITHOUT BEAVER are mostly characterized by what you don’t see. They tend to be a single straight and deep channel that doesn’t meander much through the landscape.

As a result, the water does not spread throughout the landscape and the vegetation tends to be a lot smaller, scrubbier, and drier. There is also a lack of wildlife.

When these streams do have a hydrological disturbance, like lots of rainfall all at once, it tends to result in flooding and erosion because the water doesn’t have anywhere to go.

These streams also fail to recharge our groundwater and much of the rainfall they do capture runs off into the ocean.

These streams tend to dry up very quickly in the dry season, which makes them susceptible to fire. Ventura river bottoms have actually been burning, which is not a natural occurrence.

Contrary to popular depiction, a healthy riparian ecosystem often looks less like a stream and more like a wetland. One of the first things you will notice about STREAMS WITH BEAVER is how green they are. Vegetation tends to be healthier, bigger, and more abundant. Vegetation also stays greener further into the dry season. In fact, vegetation in some of the local beaver areas I study has become even greener into the dry season.

When the beaver first moves in and builds its dam, the area often floods (that’s how ponds are made!), but after it is established, beaver ecosystems actually serve to dampen floods and make them less severe.

The heavy ponds also push water into the ground, recharging our aquifers. This groundwater is then released to the surface when pond-levels are low, buffering drought and creating year-round stream flow.

Locally, in the Los Padres where I study, we see dams between one and three feet tall and maybe 20 to 50 yards long, which is not that big for a beaver dam.

Beaver habitat is characterized by abundant wildlife. Birds, insects, and frogs all thrive here and larger mammals may use the ponds as a watering hole.

Many researchers are particularly interested in the habitat’s effect on fish like salmon and our endangered steelhead who are born in streams, live their lives in the sea, and migrate back to the stream to reproduce. The beaver ponds provide slow-water rest areas for fish swimming upstream, abundant food for the young swimming downstream, and deep water protection from predators for both. This results in increased fish numbers and size.

Beaver dams redistribute water and keep it from running off into the ocean. The dams create ponds and channels that spread water across and into the landscape.

This greening extends to surrounding farms and crops. While floods are often unwelcome by farmers, the process can help deposit richer soil, and the watery ecosystem helps their crops stay naturally greener further into the dry season.

An ecosystem that captures water can act as a natural fire break with fires fizzling out when they encounter the wetland.

You might also find humans in this verdant ecosystem. In many areas, such as wine country, beavers attract tourism.

It’s not just wild animals who benefit! Beaver make for great ranching buddies since they create watering holes for cattle and healthier grazing pasture.

And, 100 years from now, who knows what you’ll find? All wetlands create very fertile soil due to the nutrient and microbial process that occur there. Many think that much of the fertile agricultural areas we enjoy today are a result of beaver-created wetlands long ago.