Local Wine Roots Run Deep

Vineyards of Ventura County from Mission to Rancho: 1782 to 1900

Editor’s Note: We tend to think of Ventura County as a fairly new entrant as a winegrape growing region. Local historian Judy Triem shows us that’s not the case at all.

California has been in the winemaking business since 1769, with the founding of the first mission. Franciscan missionaries brought Mission grape stock from Mexico to make sacramental and table wine. The two leading varieties were the bluish-black Sonoma and reddish-black Los Angeles grape, known for being sweet and fruitier than the Sonoma. (Recent genetic analysis has determined the Mission grapes were Spanish in origin, cultivars now known as Muscat of Alexandria and Listán Prieto.)

In 1801, Father Presidente Lasuén reported that only six of the 18 missions were successful in raising grapes and pressing them into wine.

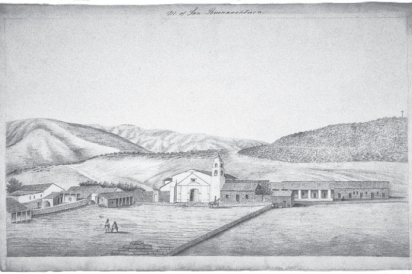

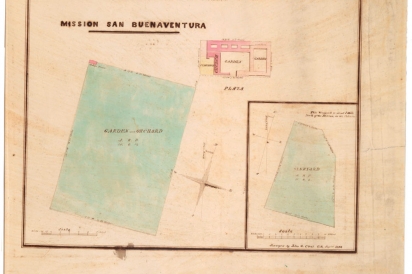

San Buenaventura Mission was one of them.

When artist Henry Miller visited the San Buenaventura Mission in 1856, he lodged at a hotel across from the church. “I tasted here the first native wine raised on the Mission, which although not clarified, tasted excellent but was very strong,” he said. The grapes were raised farther inland, about a mile to the north in the Cañada, where the grapes were protected from cool, humid ocean breezes.

By 1850, Los Angeles was the leader in viniculture in California, known as the “City of Vineyards” and producing 57,000 gallons of wine that year. Grapes were cultivated more than any other fruit. The high prices received for their wines led to Mission grapes being planted as far north as the Sacramento Valley.

VENTURA COUNTY VINEYARDS

The Topographical Map of the Valley of the Santa Clara River, published in 1860 when Ventura was still part of Santa Barbara County, showed two vineyards: the old Mission vineyard and San Cayetano, west of present-day Fillmore.

Ten years later, the California State Agricultural Census listed four grape growers in the area that was soon to become Ventura County, producing 53 tons of Mission grapes harvested for wine and brandy.

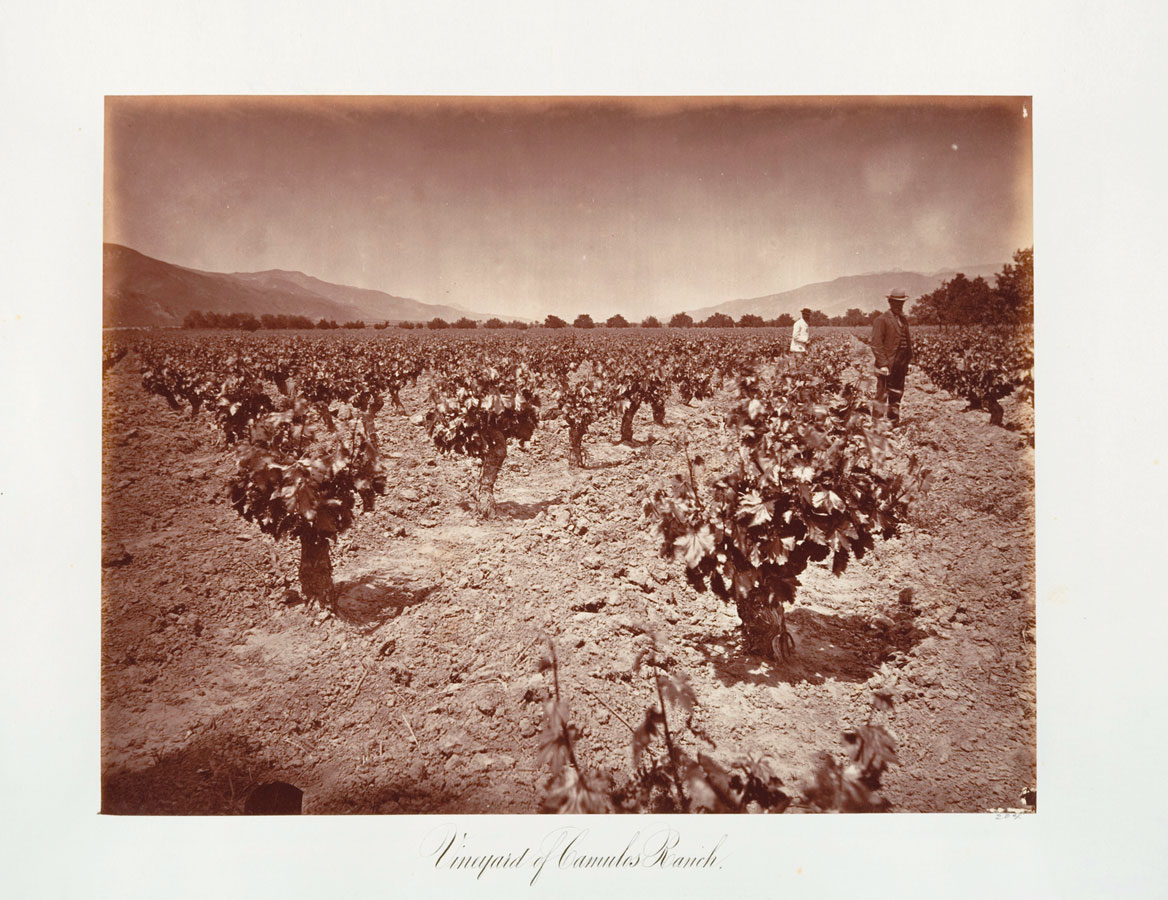

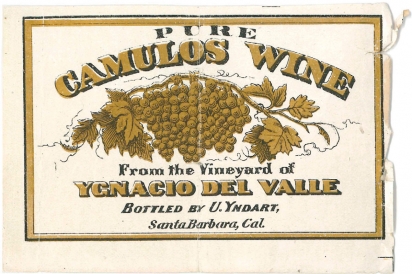

Rancho Camulos, near present-day Piru, was the largest producer listed in the 1870 census. Owner Ygnacio del Valle invested $50,000 (approximately $771,000 today) in the vineyard, which included a brick winery building built in 1867.

He raised 45 tons of Mission grapes, resulting in 6,000 gallons of wine valued at $3,000 (approximately $46,000 today) and 800 gallons of brandy valued at $1,600 (about $25,000 today). Production peaked in 1877. Del Valle had inherited Rancho Camulos in 1842, from his father, Antonio del Valle, grantee of Rancho San Francisco.

With $1,000 of capital invested, Roberto Dominguez operated a still and a wine press at the winery located on Rancho Santa Clara del Norte, probably in the vicinity of present-day Vineyard Avenue, south of the Santa Clara River. He raised 15 tons of Mission grapes, resulting in 2,500 gallons of wine, valued at $1,250, and 200 gallons of brandy, $300.

Gabriel Ruiz made wine by hand using four bull-skin wine presses with $500 capital investment at Rancho Calleguas, near present-day Camarillo. In the five months of operation, he produced 10 tons of Mission grapes, totaling 1,000 gallons of wine worth $1,500.

A fourth rancho, Tapo Vineyard, owned by Francisco de la Guerra, was also listed as growing wine grapes. No results were provided in the 1870 Census, suggesting the harvest was minimal.

There were likely other small wine-grape growers in the county, though they’re not included in the California Agricultural Census for 1870 or 1880. The Ventura Signal ’s January 18, 1879, issue listed Angel Gonzales Escandon and his wife, Francesca Sanchez, as having planted a 50-acre vineyard in 1864 on the Schiappa Pietra brothers’ ranch on Rancho Santa Clara del Norte.

By 1879, wine sold under the Schiappa Pietra name fetched 50 cents a gallon, more than double the 20 cents a gallon for Los Angeles wine. Approximately 10,000 gallons were produced in an average season. The 1879 Ventura Signal claimed it was the best wine produced in the state.

RANCHO CAMULOS VINEYARD

While the other vineyards vanished over the years, Rancho Camulos remains. You can still visit the 1,800-acre Rancho Camulos located on Telegraph Road near Piru and see the legacy Ygnacio del Valle left our county’s growing wine industry.

Prior to moving to the ranch in 1861, del Valle had been active in the Pueblo of Los Angeles, serving in both the Mexican and American government. During the 1840s, he served as a member and secretary of the junta (council) and treasurer of civil government under Governor Pio Pico. In 1850, he was elected alcalde (mayor) of Los Angeles and recorder of Los Angeles County, and later elected to the California Legislature. His home, located on the Plaza, was the center for political meetings.

By 1862, 90 acres of grapes had been planted that would bring economic success to the del Valle family, which included his wife, Ysabel, and their five children. It is unclear where he obtained his Mission grape stock, though it may have been from William Wolfskill in Los Angeles, who provided his orange stock. Del Valle purchased two 800-gallon wine tanks in the mid-1860s, indicating his wine grapes were beginning to produce; he paid an excise tax on 50 gallons of grape brandy and had a license from the Internal Revenue Service to distill at Rancho Camulos.

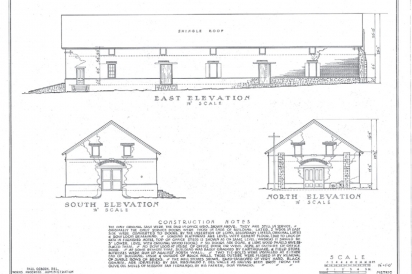

With the 1867 completion of the brick winery—which cost over $10,000—the del Valles started buying wine barrels from San Francisco. (They came to Ventura by the ship Perkins.) The copper still was loaded into a small boat just beyond the breakers off San Buenaventura and the kegs were tossed overboard to float ashore.

Not all aspects of the winery ran smoothly. In 1868, Del Valle’s old and close friend Ulpiano Yndart, a Santa Barbara merchant and owner of Rancho Nojoqui, wrote to ask if he could carry his wine. Yndart complained of the wine’s sweet quality, and said it needed to be aged for several years before it could be sold. A few years later, Yndart returned a barrel because it had once contained whiskey and had not been cleaned properly, turning the wine to vinegar.

Del Valle overcame these obstacles and nearly tripled his output by 1877, the peak year of production for his vineyard. “Camulos wines and brandies were soon a leading southern California seller,” wrote historian Wally Smith in This Land Was Ours: the Del Valles and Camulos.

Although del Valle had established a solid reputation for his brandies and wines in Santa Barbara and Los Angeles, he was still unable to compete with growers in Northern California and imported products.

His son Reginaldo, a recent graduate of what is today Santa Clara University who worked in a San Francisco law firm, advised his father he would have difficulty selling his Ventura County products in the leading stores because his prices weren’t competitive with French and other imported wines and brandies.

Though the elder del Valle corrected his issues with aging and properly cleaned barrels and sold most of his volume through Yndart, Reginaldo’s prediction was coming true.

The agricultural census for 1880 shows that while Camulos was the leader in winemaking in Ventura County—producing 5,000 gallons of wine on 60 acres of vineyards—the volume was only a third of what it was just three years earlier.

When del Valle died in 1880, his sons Juventino and Ulpiano took over the ranch management. Grapes continued to be grown until the late 1890s, but production steadily declined from its 1870s peak.

It is uncertain when the last of the vines at Rancho Camulos were removed, but when the ranch was sold to the August Rubel family in 1924 all the grapes were gone. The change started in 1900 when citrus orchards were enlarged and 44 acres of Valencia orange trees were planted. Apricots and walnut trees took over another 175 acres.

Two factors led to the decline of the winery era in Ventura County. The first was the Mission grape itself. It produced an inferior product compared to the European varieties—which were better suited for the Northern California climate—but Mission grapes continued to be widely grown here.

Also, the railroads lowered the barriers to imported competition, and altered the land economics for growers, opening Eastern markets to higher-value agricultural products from Southern California—most notably oranges and lemons.

Though the wine industry never flourished in Ventura County as it did in Los Angeles County and Northern California, it formed an essential part of our county’s early agricultural history.

It also produced the only known winery building from that era still standing, at Rancho Camulos—the county’s only National Historic Landmark.