Farming for Fashion

When we think of farming, we don’t typically think of fashion. Yet since 3000 BC, humans have been farming cotton plants and wooly fleece from sheep to make textiles. Merely 85 years ago, the disconnect between clothing and farming began as we started using petroleum to make textiles. Today, half of fibers used by the textile industry, including nylon, spandex, polyester, acrylic and acetate, come from petroleum.

The environmental consequences of this shift are astounding: The fashion industry now contributes to more than 10% of global greenhouse gas emissions, produces 20% of global wastewater, pollutes our oceans with half a million tons of plastic microfibers and fills our landfills at unprecedented rates as more than 85% of textiles are thrown away.

How do we change this dismal trajectory of the fashion industry? Local shepherds, farmers, scientists and industry leaders share what’s being done to reconnect textiles and farming in Ventura County, and how we can help mitigate the fashion industry’s impact globally.

“We need to pull the wool away from our eyes. Much of our clothing is made of microplastics. I think people are starting to understand that the way we currently make clothes is destroying our planet and destroying our health.” —Diane Anastasio

DIANE ANASTASIO, SHEPHERDESS LAND AND LIVESTOCK

“We need to pull the wool away from our eyes,” laughs Diane. She continues, seriously, “Much of our clothing is made of micro-plastics. I think people are starting to understand that the way we currently make clothes is destroying our planet and destroying our health.” Still, Diane feels “extremely hopeful about the future of wool and other natural fibers in Ventura County” as people demand more responsibly sourced clothing. Diane strives to exemplify how shepherding is a truly climate-beneficial practice: Not only do the sheep produce durable, biodegradable wool for clothing, but they also help with invasive species management, native habitat restoration, fire fuel mitigation and soil enhancement.

There are significant obstacles to growing shepherding businesses—like finding wool processing mills for smaller-scale production, finding buyers and educating consumers —but she insists “grazing and wool production present exciting alternatives to land management and petroleum-based clothing production. We need to re-educate around how ancient practices can be used in our modern world, and re-imagine what constitutes progress and innovation.”

To this end, Diane is working on a collectively managed fiber flock to encourage more shepherds and share responsibilities with people who might not otherwise have access or time, while her colleagues at Ojai-based Shepherdess Land and Livestock offer hands-on wool processing workshops.

- For more information visit www.ShepherdessLandL.co.

CINDY HARRIS, ALPACAS AT WINDY HILL

“It’s the superior fleece of the world,” says Cindy Harris matter-of-factly of her alpacas’ fleece. “It’s soft, warm, light, hypoallergenic, strong, water-repellant, durable and, most importantly, gorgeous.”

Cindy began to raise alpacas in Ventura County in 1999 when she purchased 13 acres in Somis; today, she maintains a herd of 200 alpacas and sells their fleece to small-scale clothing manufacturers nationwide. Given the fleece’s optimal characteristics and the alpacas’ evident affinity for our mild climate, why has the local alpaca fleece market not grown exponentially?

Photos by Kim Master

“Ventura County is expensive—property costs, veterinary costs, feed costs,” says Cindy. “It’s expensive to ship fleece all the way to the East Coast to be processed into fabric, but it’s currently even more expensive to develop an alpaca fleece milling facility nearby.” Moreover, “supplying commercial buyers like Nordstrom with even a line of scarves is challenging because we don’t have enough alpaca yet, and in the interim, it’s difficult to find the market for small-scale alpaca fleece.”

Nonetheless, Cindy perseveres successfully. She remains confident that the national herd size will soon grow from the current cottage-industry level to a larger, more robust commercial scale.

“I just sent 900 pounds of fleece to a guy who is going to make it into soft, warm accessories, like socks.” She spoke recently with a luxury loungewear businessman who wants to use her alpaca fleece as he shifts his company away from petroleum-based products. Cindy has also expanded her business creatively by boarding alpacas for people who don’t have the time or space, and by hosting community-oriented “fiber art retreats” and an “alpaca club” to teach people weaving skills and animal husbandry, respectively. Cindy glows with enthusiasm for her alpacas, their fleece and the heart-warming (pun intended!) connections they enable for her: “This fiber truly spoils you!”

- For more information visit www.AlpacaLink.com.

“If you are familiar with and appreciate your clothes, the hands that sheared and processed it, you are in a sense wearing the world and you feel a part of it. It’s very basic, but healing. It’s the same thing with food: When you know where it comes from, it’s an act of intimacy that’s incredible medicine in our world.” —Jenya Schneider

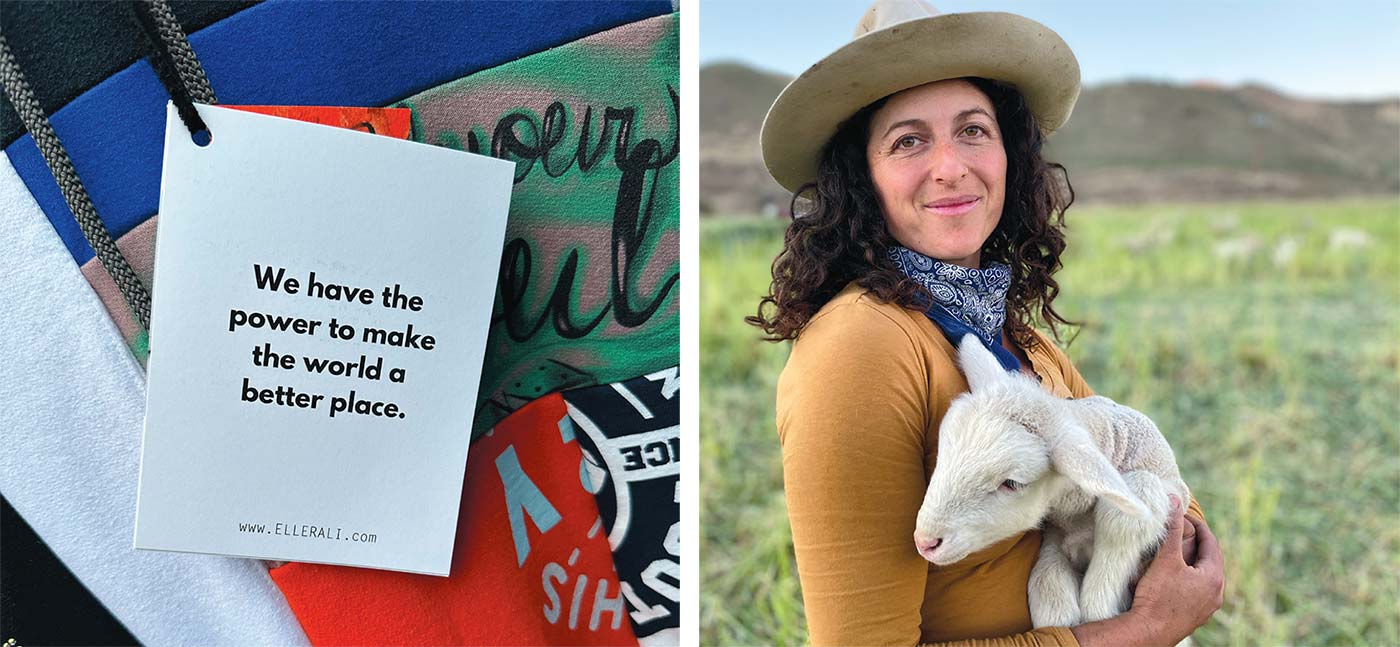

(left) Photo by Kim Master; (right) Photo by Jack Anderson

JENYA SCHNEIDER, CUYAMA LAMB

Jenya grew up “feeling as if nature was separate” from her. Perhaps to heal this detachment, she works as a shepherd.

“Connecting with sheep is a necessary, symbiotic relationship,” she says. The sheep must be sheared to survive, and, in turn, Jenya experiences deeper ties to the animals, land and her community to thrive emotionally in an otherwise alienating world.

Whereas previously she “had no idea how anything was made, where anything—from the food on the table to clothes on [her] body—came from, or what the repercussions were,” shepherding gives her a profound sense of understanding and gratitude. Her appreciation of the animals is obvious when she touts the benefits of wool: warm (“like no other material!”), moisture-wicking (“Norwegian fisherman even dip their gloves in water because it makes their gloves warmer!”), fire resistant (“A campfire spark lands on your wool sweater—no big deal!”), durable (“There’s nothing better than Grandma’s wool coat!”) and not stinky (“which is good for us hippies!”).

She emphasizes that you don’t have to be a shepherd to feel bonded to what you wear: “If you are familiar with and appreciate your clothes, the hands that sheared and processed it, you are in a sense wearing the world and you feel a part of it. It’s very basic, but healing. It’s the same thing with food: When you know where it comes from, it’s an act of intimacy that’s incredible medicine in our world.”

- For more information visit www.CuyamaLamb.com.

“Fiber hemp grows faster and creates more biomass than any crop out there. It’s really good at sequestering carbon, putting it into products. It’s biodegradable, and renewable, since you can grow it every year. It can play one of the largest roles when you are thinking about alternatives to petroleum for physical things.” —Lawrence Serbin

LAWRENCE SERBIN, HEMP TRADERS

Lawrence was one of the first people in the country to work with hemp in 1990, and “it’s taken all this time for the country to catch up!” He asserts that “fiber hemp can replace or complement almost any products made from petroleum, like plastics,” including apparel, home furnishings and building materials. Although most hemp in Ventura County has been grown for the flower variety (CBD), the market has become oversaturated, and Lawrence insists that “fiber will soon be the largest, per acreage, hemp crop.”

For the last three years, Lawrence has been working with a farmer in the Central Valley to grow fiber hemp to his specifications, and has been astounded by the crop’s success: It uses 20% less water than a neighboring pima cotton crop and grows 20 feet within six months.

“Fiber hemp grows faster and creates more biomass than any crop out there. It’s really good at sequestering carbon, putting it into products. It’s biodegradable, and renewable, since you can grow it every year. It can play one of the largest roles when you are thinking about alternatives to petroleum for physical things.”

Despite fiber hemp’s potential to replace plastic, there exist substantial obstacles to growing it locally. Fiber hemp requires a minimum of 50 acres, and ideally more, to reach an economy of scale that would make production cost effective—and this acreage is difficult to find in Ventura County. If farmers grew fiber hemp on a smaller scale, he says, they would only make $1,000 per acre profit, which is hard to justify if you can generate more than ten times that growing berries or citrus. And then there’s “the biggest obstacle: government,” says Lawrence. On a national scale, he continues, “government regulation is why we don’t have a larger hemp industry today. They flat out made it illegal to grow… Now, the government still makes us register even industry hemp crops and test them for THC before harvest, then get a background check. It ends up costing a lot of money.”

Still, Lawrence believes fiber hemp is worth consideration in Ventura County: “If people are willing to buy hemp, then we can certainly grow a lot more. It will sell itself.”

- For more information visit www.HempTraders.com.

ARIANNA BOZZOLO, PHD, RODALE INSTITUTE CALIFORNIA ORGANIC CENTER

Traditionally, the fashion industry functions in what is known as a “linear economy”: Finite resources are extracted to create textiles, the textiles are generally not used to their full potential and then the textiles are thrown away. To truly shift the fashion industry in a climate-beneficial direction, it must embody the concept of a “circular economy,” in which the clothing industry actually regenerates and improves the earth in a more holistic and cyclical framework. One of the few efforts to research this exciting framework happened to take place in Ventura County.

In 2021, the Rodale Institute California Organic Center, located on the McGrath Family Farm in Camarillo, partnered with Candiani Denim to investigate the effects of adding denim scraps, or recycled cotton, as a soil amendment. Ideally, the extra cotton would not only be reused instead of landfilled, but also would restore soil health, the epitome of a closed-loop system that fosters more regenerative agriculture.

The results were promising: Arianna Bozzolo, PhD, determined that the denim degraded within 11 weeks; soil moisture was similar or higher than soil without the denim cotton amendment; and, consequently, soil carbon levels increased due to a larger microbial population in the moister soil with the denim cover crop. Arianna concludes that “by implementing this circular and regenerative approach, the fashion industry can reduce its environmental impact, conserve resources and contribute to the regeneration of ecosystems. It’s a holistic solution that addresses both the textile waste problem and the sustainability of cotton farming.”

While Arianna admits that her Ventura County research site “may not be the place to grow cotton,” she offers that “it’s a wonderful idea.”

- For more information visit www.RodaleInstitute.org.

LESLEY ROBERTS, SOUTHERN CALIFORNIA FIBERSHED

There is no one who can tie the disparate Ventura County farming and fashion industries together better than Lesley Roberts. She is the director of Southern California Fibershed, a nonprofit that connects consumers, manufacturers, designers and ecologists to “rethink and reimagine the life cycle of garments.” So, if a clothing designer from Topanga wants alpaca wool, she’ll send them to Cindy Harris. If Diane needs to find a small-scale mill for her raw wool fibers, Lesley will help connect her with a new mill owner she met recently. If a local nonprofit needs a speaker on hemp fiber, she’ll invite a local expert like Lawrence. While Lesley’s day job is in marketing, she describes her volunteer work with Fibershed as “how I want to be in the world: connected to others, taking action and enchanted with the natural world.”

Lesley is not alone in her desire to find more connection and humanity in life—not to mention clothes that don’t damage the planet. She invited me (being the super-connector she is!) to a climate- beneficial fashion show in Ventura, to which dozens of curious locals showed up; one participant even burst into tears of joy because she had no idea so many people “felt as passionate” about fashion and climate change in the community. “Even though my work with Fibershed may not transform the fashion industry,” Lesley concedes humbly, “it matters.”

- For more information visit www.SoCalFibershed.org.

AN INTERVIEW WITH PATAGONIA FARM-FRESH FASHION IN OUR BACKYARD

By Avery Lieb

We happen to have the climate-beneficial fashion company right here in Ventura County: Patagonia. I spoke with their spokesperson, Gin Ando, to better understand what natural materials they use, how they select their materials, the viability of sourcing materials locally, their plans for the future, and advice for teenagers like me— and everyone—as we seek to make better choices for our planet.

What natural fibers does Patagonia use?

We use quite a few natural materials, including organic cotton, hemp, Yulex® natural rubber, wool and bio-based polyester.

Why do you choose to work with these particular materials?

Every material has an environmental impact, and some have far larger footprints than others. We are constantly referring to those environmental costs, analyzing how our materials are grown, what we can make with that material and how durable those products can be. Hemp, for instance, when blended with organic cotton canvas and recycled polyester is 25% more abrasion resistant than conventional duck canvas and made perfect sense to include in our workwear line. Using organic cotton came from discovering just how dirty and chemical- heavy [growing] conventional cotton is. The more we learned, the more it became a moral imperative for us to make the switch.

Where do you source your materials?

We source materials from all over the world based on their quality and how they’re acquired. Bureo, [a small sportswear business in Oxnard], for instance, supplies us with NetPlus, a recycled nylon made from abandoned fishing nets in the ocean. We’re working in India to expand adoption and capacity of farmers to grow Regenerative Organic Cotton, an organic standard that prioritizes the health and welfare of people and animals while also rebuilding healthy topsoil. Now that industrial hemp is legal to grow in the United States, we’re partnering with groups around the country to grow the domestic market as well.

Have you considered sourcing natural fibers from Ventura County?

Since we can’t source enough raw material to handle the scale we need for our products, we don’t currently have any suppliers in Ventura County.

What are the barriers to working with natural fibers?

It’s a constant push and pull when we consider the environmental costs of growing methods and the highest quality yield of a crop. While we have been using and advocating for things like regenerative organic-certified cotton, there’s no question it’s more expensive and requires more oversight. In our opinion, though, it’s worth it for the safety of the workers and welfare of the planet.

Do you feel hopeful that Patagonia is helping to transform the fashion industry away from petroleum-based products?

“Transform” is not a fully provable word from our standpoint. However, we will continue to work with and test materials like bio-based polyesters and fibers like cotton and hemp to get the most use out of them. We also believe product quality is an environmental issue and are dedicated to using synthetic materials as responsibly as possible.

Do you have any exciting materialsourcing plans for the future?

We’ll always work toward getting our entire line to be made with preferred materials (recycled materials, organic and/or regenerative materials, etc.). We can’t say anything specific now, but we’re always searching for and developing new materials from sources that close the loop.

Do you have any advice for consumers— and teenagers in particular—seeking more responsibly sourced clothing?

Everything we make and consume has an environmental impact, regardless of how “green” or “sustainable” it might seem. The most responsible thing we can do as citizens is to consume less, but if we do have to buy something, get something of high quality and use it for as long as possible. Since terms like green, sustainable and even regenerative don’t have rules for use, look for independent certifications to ensure what you’re purchasing isn’t awash in marketing terms.