Culinary Memories of Chinese New Year

By Lily You

Growing up in Taiwan in the 1960s, I remember our biggest celebration with food was Chinese New Year.

It was a festive time of tradition and where everyone’s activities centered around family and holiday preparations. When we met people we would greet them with “gong shee shin nian how,” meaning Happy New Year, in Mandarin, or the shorthand “gong shee” (happy).

Cooking started a week ahead. People would hang red posters in their doorways with “Happy New Year” or “Prosperous New Year” written in gold or black calligraphy, and visitors would arrive.

My mother would take my sisters and me to the dressmaker to choose fabrics and styles to make us New Year’s clothes, symbolizing a new start and hope for the coming year. She would take us to the hairdresser to style our hair or get it permed. Only at this special time of year would we do such things. The clothes were red, a color considered to bring good luck, or brightly colored to reflect the festive season.

The New Year’s Eve dinner is called Tuan Yuan Fun, meaning “round table dinner with family and friends.” It’s a reunion dinner, so no matter where you are you go back home to join your loved ones.

In preparation for Tuan Yuan Fun, my mother also took us to the best markets in town. Some specialized in hot-pot meats (a traditional Chinese soup with vegetables and meat cooked in a simmering pot) while others sold the best-tasting fish balls and tofu.

Each Tuan Yuan Fun, included a Chinese hot pot or Japanese sukiyaki with thinly sliced beef, pork, fish balls, mushrooms and green leafy vegetables. Sukiyaki is a traditional family meal prepared at the table, with sweet soy sauce, dipped in scrambled raw egg, and was included because of my mother’s Japanese heritage.

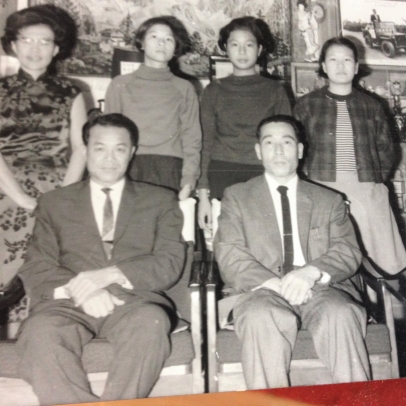

My father’s side of the family was traditional Taiwanese, meaning they were farmers. My mother’s father had worked as a train engineer in Nagoya, Japan, but when Japan lost the Second World War the family moved back to Taiwan.

Taiwan was a colony of Japan at the time, so my father, Huang Shun Shing, was sent there to receive a “proper education” when he graduated from elementary school. He did not come home until he was in his 20s. He met my mother while working at the magistrate’s office.

She grew up in Nagoya and was already in her 20s when she moved to Taiwan and had to changed her name to Chinese (Chiu Jui Shui). She didn’t speak Chinese, and no doubt suffered a great deal of culture shock.

My parents spoke Japanese at home, but father spoke Taiwanese to us. Mother later learned both languages, albeit with a heavy accent.

For Chinese New Year my parents took us back to visit my father’s family, who lived in a rural village, where they grew rice, vegetables and oranges and raised chickens and pigs. The Huangs’ big family, with seven siblings, all lived together on a large property with row houses divided by tall bamboo trees, all surrounded by a big wall.

During the visit, our aunts and uncles would entertain us, each inviting us to savor their specialty foods. The most memorable ones were my aunt’s fermented bamboo shoots and fermented winter melon preserved in jugs.

There were steamed turnip rice cakes and sweet rice dessert cakes preserved in brown sugar (made with the rice from my grandparents’ farm, ground into flour by a manual stone grinder used for special occasions).

The New Year’s Eve meal included a lot of meat—pork, a whole chicken (it had to be whole), pork sausages and fish. Having meat was a symbol of wealth, so serving it was a sign of prosperity for the host and a wish for the family in the coming year.

Beef was not allowed at the table because it was from cows that cultivated the land to provide other food for the table. My dad’s side of the family was Buddhist and asked us to light incense to pray to the Buddha. Only my father declined to participate, not believing much in traditions. He was the pioneer, the one who moved “behind the mountain” to grow tobacco in the southeast part of Taiwan. (He later became a journalist for the local newspaper and was elected to be the magistrate of the city, Taitung.)

Our family had a big round dinner table (angles are seen as bad luck, so the circular shape was important) with a Lazy Susan in the center, so everyone could reach whatever they wanted to put in the hot pot. We had different dipping sauces; one always began with soy sauce, adding spicy condiments or raw eggs.

My mother also ordered large steamed rice cakes (mochi) to serve with the New Year’s meal. Some rice cakes were sweetened and filled with red bean paste for dessert, and other rice cakes were savory. Days later, the unsweetened rice cake would harden and she would slice it into pieces an inch thick and three inches long, which she’d dip into egg batter and fry.

My mother ended each hot-pot meal by adding this mochi cake made from sweet sticky rice flour. It wasn’t until much later in life that I realized she did this because of her Japanese culinary roots.

On New Year’s Day every household would eat leftovers and shoot off fireworks. My dad would give me a red envelope with money in it for good luck in the coming year.

Blending of Cultures

As I child, I noticed a difference between the food my mother prepared at home and my neighbors’ dishes.

Sautéed burdock, braised meat with bamboo shoots and sweet soy sauce were routine at home. Yet when I went to eat with friends, there was boiled white chicken—cut up and dipped into soy sauce—or boiled pork belly thinly sliced and served with minced garlic soy sauce.

They had sliced turnip rice cake, blanched vegetables and many other dishes my mother never made. Eating with friends on the street, there were dumplings filled with meat and vegetables prepared by retired soldiers from Mainland China.

Right after I graduated college in Taiwan with a degree in music (I played the cello), I left home and emigrated to Toronto. I later moved to Vancouver, where I owned two Japanese restaurants focusing on sushi and ramen.

I did most of my growing up in North America. But it doesn’t matter how long I have lived here—my taste for food is rooted in my early years in Taiwan. Most of the meals I prepare, either Western or Eastern, contain a touch of Asia—just like the mochi cake my mother served for Tuan Yuan Fun.

Lily You and her husband, who is originally from Brainerd, Minnesota, moved to Westlake Village from Arizona. She teaches cooking classes at the Conejo Valley Adult School.