No Passport Required

Local eateries offer tantalizing tastes of Brazil and Peru

After coming to the U.S. from Venezuela as a young girl, I not only wanted to explore all that my new home had to offer. I also sought the familiarity of my language and culture wherever I could. And what better way to do that than with food?

I craved the familiar flavors of home. But with few Venezuelan restaurants in Southern California, I sought the next best thing: Latin restaurants that offered many of the dishes our countries share: plantains, black beans, empanadas and shredded beef, to name a few. Over the years, along with the comfort I’ve found in these foods, it’s been even more exciting to discover new flavors, ingredients and cooking techniques that speak to the unique set of influences that have shaped the culinary identity of our Latin neighbors.

Among the places I discovered here in Ventura County are Moqueca Brazilian Cuisine (locations in Oxnard and Thousand Oaks) and Amazon Peruvian restaurant in Moorpark. The menus of these three Latin American restaurants reflect the unique history of each country, and the different ways they combined indigenous flavors with ingredients and techniques brought from other lands. The result is a fusion of cuisines that gives each country a unique culinary identity.

MOQUECA BRAZILIAN

While most people think of churrasco (beef and sausage cooked on spits and served tableside) when they think of Brazilian food, Gloria Sarcinelli had something else in mind when she opened Moqueca in Oxnard 10 years ago.

Gloria arrived in Los Angeles from her coastal hometown of Vitória, Brazil, 13 years ago at the invitation of a friend to help with his Brazilian churrascaria, or churrasco restaurant. “I was a bank manager in Brazil, but I always did a lot of cooking. My [late] husband was the kind of person who loved food, cooking and family get-togethers.”

After three years she decided to open her own restaurant. “I decided to open a place with the kind of food I know. My husband was from a family of fishermen. He grew up fishing so if he felt like eating shrimp, for example, he would just go out on the water and get it,” says Gloria. Her son, Rodrigo Reis, adds, “We wanted to serve something representative of where we’re from.”

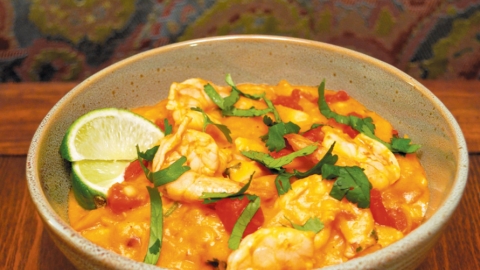

Roughly 325 miles north of Rio de Janeiro, Vitória is located in the state of Espírito Santo and enjoys a lengthy coastline along the South Atlantic coast. The area is known for its beautiful beaches and also for moqueca, Brazil’s version of jambalaya—an aromatic seafood stew made with tomatoes, garlic, cilantro, urucum (also known as achiote or annatto in North America and used to impart a reddish-orange color) and a touch of coconut milk. The mixture is cooked at 600° in a traditional clay pot and served family-style over rice.

It’s this moqueca that Gloria chose to make the signature dish of her new restaurant. Re-creating moqueca here turned out to be easier than Gloria expected.

“Being in California makes things really easy because we have a lot of influence from Latin culture: cilantro, limes, tapioca flour and coconut milk. Aside from urucum, I was surprised that I could find everything here,” Gloria says.

It’s hard to not “ooh” and “aah” when the moqueca arrives at your table, still sizzling and bubbling in the large clay pot it was cooked in. While the dish, with its variety of seafood offerings, may look rich, the sauce is surprisingly light and similar to a broth.

Introducing Ventura County diners to Gloria’s version of Brazilian food required some adjustments. “At first, people had a hard time understanding our concept. We would serve the fish with the bones, just like in Brazil. But we found out that Americans don’t want to work at their food,” she says, adding that they changed to boneless fish filets.

The success of the first restaurant inspired the second location in Thousand Oaks a little over a year ago, managed by her son, Rodrigo, and his wife, Tatiana Favoretto.

Dishes that reflect Brazil’s Portuguese heritage include colinho de bacalau, fritters made with dry-aged, salted cod, a preservation method used by the Portuguese. The cod is soaked six times to remove the salt. The fish is then mixed with creamy mashed potato and shaped into little cakes that are fried until golden. They’re served with homemade tartar sauce and a touch of malagueta oil that imparts a little bit of heat to counterbalance the richness of the sauce.

Other standout dishes on Moqueca’s menu include the traditional black bean and pork stew called feijoada. Served only on weekends, Edna Grover, chef at the Thousand Oaks location, makes her version with smoked pork sausage and a dried beef similar to beef jerky imported from Brazil.

While it makes sense that many dishes bear Brazil’s Portuguese legacy, I wasn’t expecting dishes like risotto and beef stroganoff to be on the menu.

“Many Italians and Germans came to Brazil [in the late 19th century] and relocated to our part of the country,” says Gloria, who is of Italian descent. Dishes like scallops on the half shell, risotto de mariscos (seafood risotto) and linguine al vongole reflect this heritage.

And the stroganoff?

“Stroganoff is very popular in Brazil,” says Gloria. “But we always serve it with rice. One of my customers asked if we could serve it with noodles. … So now it is part of the menu, and it is one of the favorite dishes other than the moqueca.”

PERUVIAN PALATE

Nestled in a residential neighborhood near Moorpark College is Amazon Peruvian, a restaurant that also reflects the historical touch points that have shaped Peru’s food and culture.

Owner Nicanor (Nick) Aguirre came to the U.S. in 1985 to stay with family after graduating from college.

“I wanted to learn English and to find more opportunities for work than in Peru,” he says. Nick is from Chimbote, a port city in northern Peru, once known as the anchovy capital of the world.

Over the years, Nick worked in a variety of businesses, but cooking was a consistent presence.

“I always liked to cook at home and my friends always encouraged me to open a restaurant.”

Eventually Nick and his nephew, Jonathan Aguirre, decided to explore the idea. Jonathan is from Huánuco in Central Peru.

“I went to work for other restaurants to learn how to manage one before starting my own. My nephew also went to work in restaurant kitchens to learn to cook in a restaurant setting.” Nick also collaborated with his wife, Victoria, to fine-tune the recipes from their home in Peru.

Nick’s new restaurant would have all the typical Peruvian dishes, but one in particular required special equipment: Pollo a la brasa, or rotisserie chicken, is cooked over wood coals in a special oven that Nick imported from Peru. This style of cooking was made popular in the 1950s by a Swiss chicken farmer in Lima named Roger Schuler, according to various sources.

“It’s lined with bricks that retain the heat while the chicken rotates inside,” says Nick. “In Peru, avocado wood is used along with other woods, giving the chicken a smoky flavor.”

If you’re not familiar with Peruvian food, the menu can seem a little daunting at first. Not only do some ingredients have different names in Peru than in other Spanish-speaking countries, but the cuisine features styles of cooking that are very different from typical South American dishes.

To begin with, it was in Peru that Spanish conquistadores discovered the potato and took it back to Europe. Peru is also unique in the varieties of native corn and tomatoes that are grown, for example. These ingredients feature prominently in the cuisine.

Peru is also one of several South American countries that saw a large influx of Chinese and Japanese immigrants during the 19th century. And while the impact of this migration from Asia can be seen to varying degrees in the cuisines of many South American countries including Mexico, Cuba and Brazil, Asian ingredients and techniques have become an integral part of Peru’s culinary DNA.

“Chinese and Japanese immigrants have shaped and transformed Peruvian cuisine over the past two centuries, making ginger and soy sauce as quintessentially Peruvian as quinõa and potatoes,” notes an article by the Center for Foods of the Americas.

The result are dishes that both honor the native ingredients of the land and integrate new ingredients and techniques for a true fusion cuisine.

Lomo saltado, one of the Peru’s most popular dishes, is very similar to an Asian stir-fry. Small strips of steak are quickly seared over high heat with red onions, tomatoes, cilantro and a little soy sauce, then tossed with french fries (yes, like American fries) and served with rice. It’s hard to order anything else on the menu after eating this dish, in my opinion.

Arroz chaufa, a type of fried rice served with seafood or chicken, is another example of the Asian influence on the cuisine.

Ceviche is believed to have originated in Peru. The popular dish is a tangy mixture of raw fish—like what you see in Japan—marinated in citrus juices.

Pescado a lo macho is a crispy breaded fried fish fillet served with a hearty seafood sauce made with shrimp, squid, tomatoes, garlic, aji (Peruvian chili pepper) and a touch of cream.

Aguadito de pollo is a chicken soup with potatoes, corn and peas. Infused with cilantro, the broth is a beautiful green. (See recipe on page 38.)

These restaurants take us to South America, while at the same time reminding us of the limitless range of cuisines from around the world that we’re lucky enough to enjoy right here in Ventura County.