Sake Primer

When I was in college, sake was a drink served in a shot glass at sushi restaurants, and it may or may not have been suspended with chopsticks above a Japanese beer. You pounded the table to release the wooden suspension and chugged it.

This, my friends, is not the real sake experience.

I say this as a sommelier who was so taken by sake that I pursued a Level 1 sake certification. While studying the age-old spirit, I realized sake is misunderstood in the U.S., and the sake-making process is both more complex and simpler than winemaking.

What is sake?

Simply put, sake is a Japanese alcoholic beverage made from just four ingredients: steamed white rice, kogi (fermented cooked rice or soybeans), yeast and water.

All alcoholic drinks have been through a fermentation process, where sugar is converted into alcohol. With wine, the grapes have everything needed for fermentation including the sugar; however, rice does not. This is where kogi comes in. Kogi is a magical mold that contains an enzyme that converts the carbohydrates to sugar. Meaning sake doesn’t need additional sugar to ferment.

Generally, sake is anywhere between 15% and 17% alcohol by volume (ABV), much more comparable to wine than to the tequila or whiskey you might expect in that falling shot glass I described earlier. (To put that into perspective, a California Cabernet can easily be 14% to 15%.)

How is sake made?

Without getting wonky about the sake-making process, which predates most other alcohol production, sake starts with polishing 100% to 50% of the rice. (The more the rice has been polished, the lower the ABV.)

The rice is washed, soaked and steamed, the same way you’d make sushi rice at home. After the rice has cooled, the kogi is added to a fermentation tank with the water and yeast.

Nearly all of sake’s aroma comes from the yeast strain that is added to the fermentation process. This can be a hyper-local yeast (naturally occurring in the air around the vats), or one that is purchased and is more refined, stable and consistent.

Now choices are made, depending on the style of sake. Will the sake be filtered? Will distilled alcohol be added? Or water to decrease the percent of alcohol? Will it be pasteurized?

How do you drink sake?

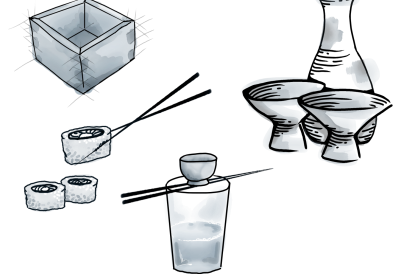

This depends on how traditional you want to be. The most traditional way is with a masu, Japanese for “small box”; historically, masu were used for measuring rice, but they were also used for ceremonial occasions. Today, sake can be served in wine glasses (a tulip shape helps enhance the aromas). At home, I drink sake from a wine glass or, if I feel fancy, from a two-ounce wooden vessel.

Unlike most wines, with sake you have the luxury of enjoying it at different temperatures, and who doesn’t love that? So I encourage you to have a glass of chilled sake in the summer, and a glass of warmed sake in the winter.

DRINK THIS IN

You may be wondering how to pick a bottle of sake and know its characteristics. To help, Adam Hart created this handy sake cheat sheet with food pairing ideas so you can find just the right sake to go with your meal.

Don’t feel you need to spend a lot on a bottle. Hart says “cheap” sake isn’t bad quality; it just isn’t as refined as the more expensive styles.

Junmai and Honjozo: Rice is polished to 70% and has cereal and lactic aromas with more acid and umami taste. Junmai means “just rice,” and honjozo is essentially junmai with the addition of distilled alcohol. In Japan, junmai and honjozo (lower tier) are served more widely. Serving Temp: Chilled, room temp or warm (no more than 122ºF) Pairing: Sushi or any raw fish dish Junmai Ginjo and Ginjo: Rice is polished to 60% and has fruitier, more floral aromas. Ginjo, like honjozo, has distilled alcohol added. Serving Temp: Chilled or room temp (if that is your preference) Pairing: Fresh vegetables and salads with higher-acid vinaigrettes. Junmai Daiginjo and Daiginjo: Rice is polished to 50% but retains the same fruity, floral aromas. Distilled alcohol is added to daiginjo. Serving Temp: Chilled or room temp (if that is your preference) Pairing: Blue cheese, gruyere cheese or Romano cheese Nama-Zake: Unpasteurized sake Serving Temp: Chilled or room temp (if that is your preference) Pairing: Fois gras or other liver pâté Nigori: Roughly filtered and can appear cloudy Serving Temp: Best served chilled but can be warmed Pairing: Spicy foods or sweet barbecue sauce Sparkling: Carbon dioxide is added to create bubbles Serving Temp: Chilled Pairing: Fresh fruits and berries Koshu: Must be aged more than three years and is sometimes caramel colored Serving Temp: Room temp Pairing: Grilled fishSommeliers struggle to pair wines with Asian cuisines, and at times it feels like forcing a square peg into a round hole. Sake is the perfect pairing for these dishes.

The bottom line is that sake, like any fermented beverage, is meant to be enjoyed, so don’t get too wrapped up in labels or processes. If you enjoy it, drink it!

LOCAL SAKE STAKEOUT

For relatively low cost, you can pick up small bottles of different sakes from a local bulk liquor store to enjoy over time. Just remember that sake should be consumed within one week of opening and one year from its production date (unless it is koshu).

For a restaurant sake and food experience, Hart recommends Gotetsu (Gotetsu805.com/restaurant) in Ventura and Onyx at the Four Seasons (FourSeasons.com/WestlakeVillage) in Westlake Village. Both have a great selection of sakes and knowledgeable staff, he says.